Introduction

Liver flukes, a group of flatworm parasites, might not be a household name, but they’re a big deal in the worlds of health and agriculture. These parasites target the liver and bile ducts of mammals—including humans—and cause problems ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening diseases. They also hit the livestock industry hard, costing billions annually in lost productivity.

This guide dives deep into the world of liver flukes, covering everything from their lifecycle and health impacts to prevention and the latest research.

What Are Liver Flukes?

Liver flukes are parasitic flatworms that live in the livers of their hosts. They’re part of a group called Trematoda, and their name gives away their most common hiding spot—the liver. While there are many types, the four big players are:

- Fasciola hepatica: Also known as the common liver fluke, it mostly infects livestock like sheep and cattle but occasionally jumps to humans.

- Fasciola gigantica: This is the larger cousin of F. hepatica and thrives in tropical areas.

- Clonorchis sinensis: Called the Chinese liver fluke, it’s common in East Asia and infects humans.

- Opisthorchis viverrini: Found in Southeast Asia, this fluke is particularly notorious for increasing the risk of bile duct cancer.

What Do Liver Flukes Look Like?

Liver flukes have a flat, leaf-like body designed for parasitic life. Here are some key features:

- Size: Fasciola species are around 2–3 cm long, while Clonorchis and Opisthorchis are smaller, about 1–2 cm.

- Attachment Tools: They use suckers to latch onto the liver and bile ducts.

- No Digestive System: Instead of a traditional gut, they absorb nutrients directly through their body surface.

- Reproductive Powerhouses: Liver flukes are hermaphroditic, meaning they have both male and female reproductive organs, making them incredibly efficient at reproducing.

How Do Liver Flukes Live?

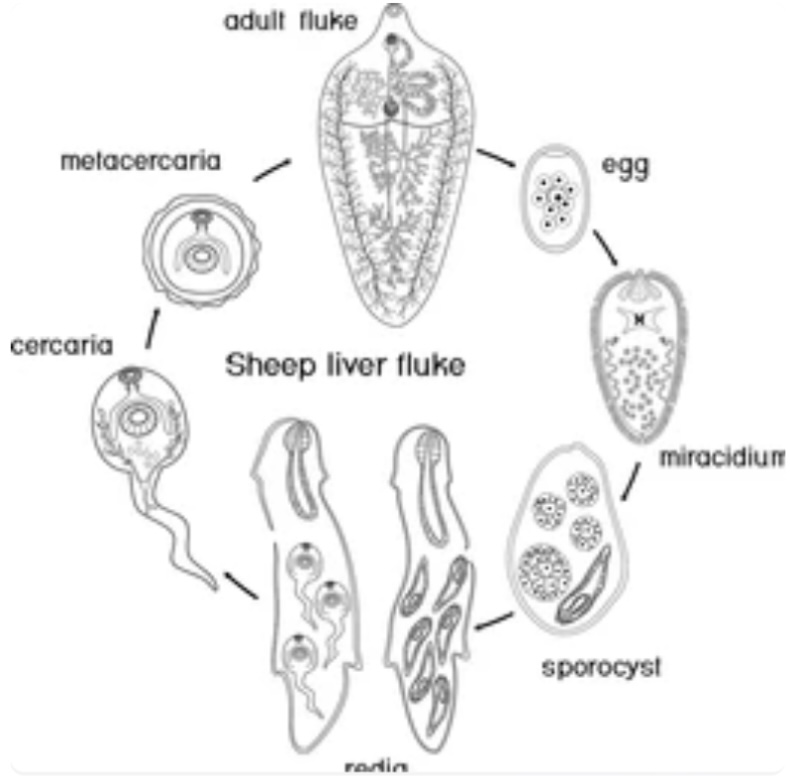

Liver flukes have a fascinating but complex lifecycle that involves two hosts—a snail and a mammal.

- Egg Stage: Adult flukes in the liver lay eggs, which are excreted in the host’s feces.

- Hatching in Water: The eggs hatch into free-swimming larvae called miracidia when they hit water.

- Snail Host: These larvae find freshwater snails and develop through several stages, eventually turning into free-swimming cercariae.

- Vegetation Hitchhikers: The cercariae leave the snail and encyst on plants as metacercariae, waiting for a mammal to eat them.

- Final Host (Humans or Livestock): When infected plants are eaten, the metacercariae excyst in the intestines, migrate to the liver, and mature into adult flukes.

Where Are Liver Flukes Found?

Liver flukes are a global problem, but they thrive in certain regions:

- Fasciola hepatica: Found in temperate areas like Europe, North America, and parts of Africa.

- Fasciola gigantica: Prefers the tropics, especially in Asia and Africa.

- Clonorchis sinensis: Prevalent in East Asia, particularly China, Korea, and Vietnam.

- Opisthorchis viverrini: Found in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

How Do Liver Flukes Affect Us?

Humans

For humans, liver flukes cause conditions like fascioliasis, clonorchiasis, or opisthorchiasis, depending on the species. Symptoms can range from mild to severe:

- Early Signs: Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and a swollen liver are common.

- Chronic Problems: Long-term infections can cause bile duct inflammation, jaundice, and even liver cancer in severe cases.

Livestock

In animals like sheep and cattle, liver flukes cause fasciolosis, leading to:

- Weight loss and reduced milk production.

- Poor growth and reproduction.

- In severe cases, death due to liver damage and anemia.

How Are Liver Fluke Infections Diagnosed?

Detecting liver flukes involves several methods:

- Microscopic Stool Tests: Checking for eggs in stool or bile samples.

- Blood Tests: ELISA tests can detect antibodies against liver flukes.

- Imaging: Ultrasounds, CT scans, or MRIs can reveal liver damage.

- DNA Tests: PCR methods offer highly specific detection.

How Can We Prevent and Control Liver Flukes?

In Humans

- Avoid Raw or Undercooked Foods: Especially freshwater fish and plants in endemic areas.

- Better Sanitation: Preventing fecal contamination of water sources can reduce transmission.

- Health Education: Raising awareness in affected communities is vital.

In Livestock

- Deworming: Using effective antiparasitic drugs like triclabendazole for Fasciola infections.

- Snail Control: Reducing snail populations with molluscicides or habitat modification.

- Vaccines: Research is underway, but no commercially available vaccine exists yet.

Why Do Liver Flukes Matter?

Liver flukes don’t just cause health problems—they also have a big economic impact:

- For Livestock: Losses from fasciolosis exceed $3 billion globally each year.

- For Humans: Over 17 million people are infected worldwide, with significant health burdens in endemic areas.

What’s New in Liver Fluke Research?

Recent advances in science are shedding light on these parasites:

- Genomics: Scientists are decoding the liver fluke genome to find new treatment and vaccine targets.

- Flight of the Snail: Climate change is expanding the range of liver flukes by creating more suitable habitats for their snail hosts.

- New Drugs: Research is focusing on alternatives to current treatments, as resistance to triclabendazole is emerging.

Conclusion

Liver flukes may be tiny, but their impact is anything but. From causing diseases in humans to crippling the livestock industry, they’re a problem we can’t ignore. Fortunately, with better diagnosis, treatment, and prevention strategies, we’re getting closer to controlling these parasites. Whether through science, education, or improved hygiene, tackling liver flukes head-on is essential for healthier people, animals, and economies.

References

- Keiser, J., & Utzinger, J. (2009). Food-Borne Trematodiases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. Link

- Mas-Coma, S., et al. (2005). Human Fascioliasis: An Emerging Infection in Europe?. Infection, Genetics, and Evolution. Link

- World Health Organization. (2022). Foodborne Trematode Infections. Link

- Torgerson, P., & Macpherson, C. (2011). Impact of Helminths on Livestock Productivity. Veterinary Parasitology. Link

Discover more from ZOOLOGYTALKS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.